- Home

- Dan Gutman

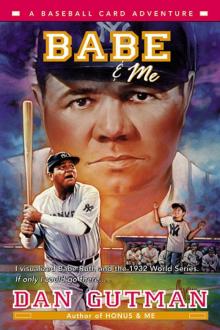

Babe & Me

Babe & Me Read online

Babe & Me

A Baseball Card Adventure

Dan Gutman

Dedication

Dedicated to the real heroes—

teachers and librarians

Contents

Dedication

The Mystery

1

The Tingling Sensation

2

Use Your Head

3

Going Back…Back…Back…

4

Blown Off Course

5

Hooverville

6

The Babe

7

Three Strikes You’re Out

8

Payday

9

Living Big

10

Playing with History

11

Dumb Luck

12

A Secret Revealed

13

Fathers and Sons

14

Governor Roosevelt

15

Game Three

16

The Called Shot

17

Something Better

18

Slipping Away

19

Attack!

To the Reader

Permissions

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Other Books by Dan Gutman

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

The Mystery

IT’S THE GREATEST MYSTERY IN THE HISTORY OF SPORTS. It’s one of the greatest mysteries of the twentieth century.

And I was the only person in the world who could solve it.

These are the facts:

The date: October 1, 1932

The place: Wrigley Field, Chicago, Illinois

The situation: The Chicago Cubs and New York Yankees played Game Three of the World Series on this day. In the fifth inning, Babe Ruth belted a long home run to straightaway centerfield.

This is the mystery: Did the Babe “call his shot”? Or not?

According to legend, just before he hit that homer, Babe pointed to the centerfield bleachers and boldly predicted he would slam the next pitch there.

I’ve played a lot of baseball. Maybe you have, too. Hitting a baseball is not easy. Hitting a baseball to one side of the field or the other on purpose is very hard. And saying you’re going to hit a home run on a specific pitch and to a specific part of the ballpark with the pressure on, well, that’s just impossible. A batter who calls a shot like that is either incredibly lucky, crazy, stupid, or gifted. Maybe all four.

The closest witnesses to Babe’s called shot—the Cub and Yankee players—disagreed. Some said Babe called his shot; others said he was only pointing and yelling at the Cub pitcher, Charlie Root. Some said the whole story is a myth that the press dreamed up to glorify Babe Ruth.

A few years ago somebody found a fuzzy home movie of Ruth at the plate at that moment.

A few years ago somebody found a fuzzy home movie of Ruth at the plate at that moment. He pointed all right, but it’s impossible to tell exactly where he was pointing.

People said it didn’t matter if Babe called his shot or not. All that mattered is that he hit the home run.

Well, it mattered to me. I wanted to know the truth.

There was only one way for a human being to solve this mystery—to travel back to October 1, 1932, and see what happened.

The amazing thing is, I could do it.

Joe Stoshack

1

The Tingling Sensation

IT WAS ABOUT EIGHT YEARS AGO—WHEN I WAS FIVE— that I discovered baseball cards were sort of…oh, magical to me.

It was past my bedtime, I remember. I was sitting at the kitchen table with my dad. This was before my mom and dad split up, before things got weird around the house. Dad was showing me his collection of baseball cards. He had hundreds, a few of them dating back to the 1920s.

My dad never made a lot of money working as a machine operator here in Louisville, Kentucky. I think he spent all his extra money on his two passions in life—fixing up old cars and buying up old baseball cards. Dad loved his cars and cards. They were two of the things Dad and Mom argued about.

Anyway, we were sitting there at the table and Dad handed me an old card.

“That’s a Gil McDougald card from 1954,” Dad said. “He was my hero growing up. What a sweet swing he had.”

I examined the card. As I held it in my right hand, I felt a strange tingling sensation in my fingertips. It didn’t hurt. It was pleasant. It felt a little bit like when you brush your fingers lightly against a TV screen when it’s on.

I felt vibrations. It was a little frightening. I mean, it was only a piece of cardboard, but it felt so powerful.

“Joe,” my dad said, waving his hand in front of my face, “are you okay?”

I dropped the card on the table. The tingling sensation stopped immediately.

“Uh, yeah,” I said uncertainly as I snapped out of it. “Why?”

“You looked like you were in a trance or something,” Dad explained, “like you weren’t all there.”

“I felt like I wasn’t all there.”

“He’s overtired,” my mom said, a little irritated. “Will you stop fooling with those cards and let Joey go to bed?”

But I wasn’t overtired. I didn’t know it at the time, but a baseball card—for me—could function like a time machine. That tingling sensation was the signal that my body was about to leave the present and travel back through time to the year on the card. If I had held the card a few seconds longer, I would have gone back to 1954 and landed somewhere near Gil McDougald.

After that night I touched other baseball cards from time to time. Sometimes I felt the tingling sensation. Other times I felt nothing.

Whenever I felt the tingling sensation I dropped the card. I was afraid. I could tell something strange was going to happen if I held on to the card. I didn’t know what would happen, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to find out.

Gradually, I discovered that the year of the card determined whether or not it would cause the tingling sensation. Brand-new cards didn’t do anything. Cards from the 1960s to the 1990s didn’t do much. But I could get a definite buzz from any card from the 1950s. The older the card, I discovered, the more powerful the tingling sensation.

One day, I got hold of a 1909 T-206 Honus Wagner card—the most valuable baseball card in the world. The tingling sensation started the instant I picked up the card. It was more powerful than it had been with any other card. For the first time, I didn’t drop the card.

As I held the Wagner card, the tingling sensation moved up my fingers and through my arms, and washed over my entire body. As I thought about the year 1909, the environment around me faded away and was replaced by a different environment. It took about five seconds. In those five seconds, I traveled back through time to the year 1909.

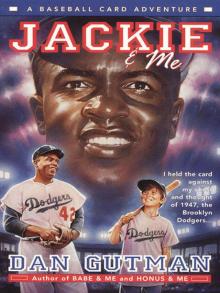

What happened to me in 1909 is a long story, and I almost didn’t make it back. After that, I didn’t think I would ever travel through time with a baseball card again. But once you discover you’ve got a special power, it’s hard not to use it. For a school project, I borrowed a Jackie Robinson card from a baseball card dealer and sent myself back to the year 1947.

I nearly got killed in 1947, and my mom grounded me. She didn’t make me stay in my room or anything like that, but she did make me stay in the present day.

“No more time traveling!” she ordered.

But, like I said, when you’ve got a special power, you want to use it.

2

Use Your Head

“SMASH IT, STOSHACK!” ONE OF MY TEAMMATES YELLED as I pulled on my batting glove. “Hit one outta here so we can g

et outta here.”

I snorted. Nobody has ever hit a ball out of Dunn Field, the park where most Louisville Little League games are played. It’s not because the outfield wall is so deep. It’s because it’s so high. The plywood fence in left-, center-, and rightfield extends twenty or thirty feet off the ground.

The wall is plastered with ads for just about every hardware store, car dealership, dry cleaner, and supermarket in Louisville. The Little League sold a lot of ads this year, so they made the fences even higher to have a place to put them all.

Casey Tyler—one of the kids on my team—hit a ball off the wall once. In left center. He only got a double out of it because the ball bounced right to the centerfielder. I hit pretty good—I mean, pretty well—but I can’t imagine hitting one out of Dunn Field.

“Be aggressive, Joey,” Coach Zippel hollered, cupping his hands around his mouth. “That baseball is your worst enemy! Slam it.”

My team, the Yellow Jackets, was down by two runs. There were two outs in the bottom of the sixth inning, which is all we play in the league for thirteen-year-olds. As I stepped into the batter’s box, Casey Tyler took a lead off second base and Kevin Dougrey edged off third.

“Run on anything!” Coach Zippel yelled. “Two outs.”

I pumped my bat back and forth a few times. The pitcher wasn’t so tough. I had already singled off him. A solid hit would score both our runners and tie the game. An out of any kind would end the game, with our team losing.

“Smack one, Joey!” my mom shouted. She was sitting in the “mom” section of the bleachers. That’s where all the moms sit. I don’t think any of them are big baseball fans, but they like to get together and gossip and stuff while we play.

The dads are usually around the field, shouting encouragement and advice to us. Most of the dads show up for our games if they can. Even though he loves baseball, my dad has never been to one of my games. He says he can’t get off from work, but I think it’s really because he doesn’t want to see my mom unless he has to.

In fact, we live only 250 miles from St. Louis, but my dad has never even taken me to a Cardinals game—or any big-league game.

As I dug a cleat into the dirt, I snuck a peek at the fielders. I bat lefty, so the defense had shifted to the right a little.

The third baseman, I noticed, was playing almost right on the foul line and way back—just behind the third-base bag. He wanted to keep Kevin close to the base, I knew, and he wanted to prevent a double or triple down the line.

A thought flashed through my brain: I could drop a bunt in front of that guy and beat it out. Kevin would score from third easily and Casey would advance to third. It would take everybody by surprise.

I didn’t want to talk my idea over with Coach Zippel. If the other team saw me go over to him, they might suspect something was up. Besides, there was no time. The pitcher was going into his windup.

I waited until the last possible instant to square around and slide my hand up the barrel of the bat.

“He’s layin’ one down!” the coach of the other team screamed.

The pitch was right over the plate, just where I like it. I held the bat out the way Coach Zippel taught us in our bunting drills. You’re supposed to sort of “catch” the ball with the bat. The idea is to tap it just hard enough so the catcher can’t pounce on it, but softly enough so it stops far in front of the third baseman. It was a good bunt, I thought.

When the ball hit the bat, I broke for first. The third baseman made a dash toward the plate as soon as he saw me squaring around to bunt.

From the corner of my eye, I saw him reach down and scoop up the rolling ball bare-handed. In one motion, he whipped it underhanded toward first. He made a great play, but I thought I had it beat. As my foot hit the first-base bag, I heard the ball pop into the first baseman’s mitt.

“Out!” bellowed the umpire. “That’s the ball game!”

“What?” I yelled, turning around to find the ump. “I beat it out! I beat the ball to the bag!”

“Son, I had the best seat in the house,” the ump said, “and you were out.”

“Oh, man!”

The kids on the other team were pounding the third baseman on his back and congratulating him on his great play. My teammates just packed up their gear. Nobody gave me a hard time about it, but when I got back to the bench, Coach Zippel pulled me aside.

“Why’d you bunt, Joey?” he asked, his arm on my shoulder. I could tell he was angry, but he was doing his best not to show it. The coaches in our league are supposed to encourage us, even when we mess up.

“I saw the third baseman playing way back,” I explained. “I thought I could drop a bunt in front of him.”

“But, Joey, you’re a good hitter. You could have tied the game for us with a hit. Even if you had been safe at first on the bunt, we only would have scored one run. We needed two. And Frankie was up next.”

Frankie Maloney was our worst hitter. The coach didn’t come out and say it, but we both knew there was no way Frankie would have driven in the tying run. That was my job. I messed up.

“I hadn’t thought of that,” I admitted. “I’m sorry, Coach.”

“Don’t be so afraid to take a big old rip at the ball, Joey,” the coach advised me. “If you would only let loose, there’s no telling how hard you might hit it.”

All the way home from the game, I sulked. The coach was right. I was too cautious. I wanted to hit the ball hard, but when the pressure was on and the pitch was coming in, something stopped me. So I usually took a halfhearted swing. Or I thought up some excuse to bunt.

“It was a beautiful bunt, honey,” Mom said, trying to cheer me up as we pulled into our driveway. “You did the best you could.”

Mom doesn’t understand baseball. Everybody makes an error from time to time, but there’s no excuse for a guy to make a dumb decision like I did. I never should have bunted. I should have swung away. Mom just saw the play, not the strategy.

My mom is Irish and my dad is Polish. Not that it matters or anything, but I thought you should know a little about me. Mom is a nurse at the University of Louisville Hospital. I don’t have any brothers or sisters, though I guess I would have if my folks had stayed together. I’ve got a couple of cousins, but they live in Massachusetts and we hardly ever get together.

“Your father is coming over after dinner,” Mom said as she cleaned a carrot for dinner. “He says he has something he needs to talk to both of us about.”

“What is it?”

“He wouldn’t tell me,” Mom said, digging into the carrot a little harder than was necessary.

I don’t know why my parents got divorced. I’m not sure if my mom or dad knows, either. One time I asked my mom about it, and she said my dad was angry all the time. He would never say what was really bothering him. Like it was some big secret or something. For years Mom tried to get him to talk about what troubled him, but finally she decided she just couldn’t live with him anymore.

Dad lives in an apartment across town. He comes over to see me from time to time, but I don’t feel all that comfortable with him. I guess I blame him for divorcing Mom, even if it was her idea.

“How’d you do in your game today, Butch?” Dad asked when I opened the door. He’s always called me Butch.

I felt like telling him he could have seen for himself how I did, if he had only come to the game. But I didn’t want to set him off.

“I did okay,” I said unenthusiastically. “Got a hit.”

“That’s my boy.”

“What did you want to talk to us about, Bill?” Mom asked. She never liked to chitchat with Dad.

Dad shuffled his feet a little and looked down uncomfortably, a sure sign of bad news.

“I got laid off again,” he said finally. “Business is slow. They had to get rid of people. Naturally, I was the first to go. I got no luck.”

“You’ll get another job, Bill,” Mom said.

“Yeah? What do you know? Who’s gonna h

ire me?”

Dad’s eyes flashed anger. It was like he was blaming Mom for losing his job, when all she was trying to do was comfort him.

“The newspaper is filled with ads for guys who do what you do,” Mom tried again.

“Sure, if I want a crummy job that pays nothin’.”

Mom sighed. When Dad got into one of these moods, there was nothing anyone could say or do that would make him cheer up. Wearily, Mom took out her checkbook and started writing.

“I didn’t come here to ask for more money, Terry.”

“Just take it,” Mom said, handing him a check.

He ripped the check in half and handed it back to her.

“Joe,” Dad said, turning to me, “do you still have that old Babe Ruth card I gave you a while ago?”

“Sure, Dad.”

“Would you be really upset if I asked for it back?”

It must have been really tough for him to ask that. He gave me the Ruth card as a present when I turned twelve. He must be selling off his card collection, I figured. He must need money pretty badly.

“Don’t ask Joey to return a gift,” Mom lectured him. “I’ll lend you money.”

“Quiet, Terry.”

“I’ll get the card,” I said.

I keep my older, more valuable cards in clear plastic holders. This is partly to protect them and partly because I get that tingling sensation when I touch them. I wouldn’t want to send myself back through time accidentally.

The Ruth card was the gem of my collection. It was from 1932 and very rare. My dad got the card for next to nothing from some lady who’d sold her husband’s old card collection after he died. She had no idea it was valuable. The card was in good condition. I looked it up in a book once, and the book said it was worth ten thousand dollars.

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

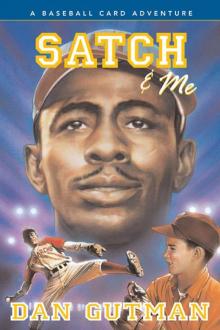

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

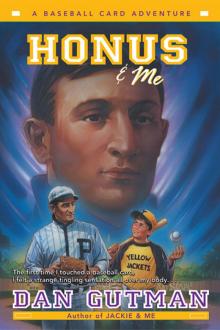

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

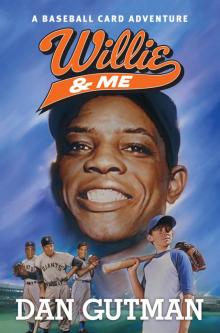

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!