- Home

- Dan Gutman

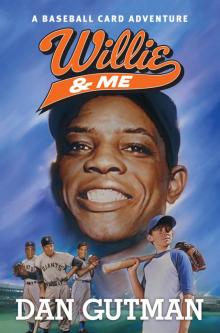

Willie & Me

Willie & Me Read online

Willie & Me

Sometimes you can change history.

And sometimes history can change you.

Dedication

To Ray and Eric Dimetrosky

Acknowledgments

THANKS TO MY EDITORS OF THIS SERIES SINCE 1996—Andrew Harwell, Barbara Lalicki, Rachel Orr, Elise Howard, Stephen Fraser, and Stephanie Siegel. Also my deepest gratitude to Liza Voges, Nina Wallace, Howard Wolf, Craig Proturny, David Kelly, Eric Levin, Robert Lifson, Joanne Pure, Pat Kelly and the good folks at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, SABR, Zach Rice, Steve Chorney for the fantastic covers, and Joshua Prager. And, of course, all the folks at HarperCollins.

Epigraph

Now it is done, now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again.

—Red Smith,

New York Herald Tribune,

October 3, 1951

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Introduction

1. Flip Flops

2. Happy Birthday

3. One Lousy Pitch

4. “I Ain’t Dead Yet”

5. Another Visitor

6. For the Fun of It

7. You Only Live Once

8. The Right Thing to Do

9. Baseball Is a War

10. Trapped

11. The Butterfly Effect

12. A Good Day

13. Unintended Consequences

14. A New Mission

15. Like Magic

16. Another Birthday Present

17. Sometimes History Can Change You

Facts and Fictions

Back Ad

About the Author

Books by Dan Gutman

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

WITH A BASEBALL CARD IN MY HAND, I AM THE MOST POWERFUL person in the world. With a card in my hand, I can do something the president of the United States can’t do, the most intelligent genius on the planet can’t do, the best athlete in the universe can’t do.

I can travel through time.

—Joe Stoshack

“YOU’RE THE MAN, STOSH!” MY TEAMMATE LEON GREENE shouted through cupped hands from second base. “Let’s do this thing, and get outta here.”

It was drizzling when I came to bat in the sixth inning at Dunn Field. I hate playing in the rain. You can’t dig your feet into the dirt of the batter’s box, and it’s easy to slip in the mud when you break for first base. I wiped my hands on my pants. The bat was slippery.

But then, so was the ball. I looked up at the Ace Hardware pitcher. He was a lefty, like me. His name was Lenny Breakowitz, or something like that. He didn’t look too thrilled about playing in the rain either. His first pitch had bounced ten feet in front of the plate. Ball one. He was blowing on his fingers, trying to dry them off.

Now he was ready, and so was I. The pitch looked fat. I took a rip at it, but missed. Swung too early. One and one. Take a deep breath.

The rain seemed to be coming down harder. I wiped my eyes with my sleeve. Why doesn’t the lady ump call the game? It’s not like it’s the World Series or anything. The game doesn’t mean anything. Let’s go home.

Breakowitz looked in for his sign, nodded, and went into his windup. The pitch looked outside to me, so I let it go. Fortunately, the ump agreed. Ball two.

“Drive me in, Stosh!” Leon hollered from second. “Come on!”

I had almost forgotten that Leon was there, because I was looking at my new cleats. They were soaked all the way through. My mom was going to go ballistic. She just bought the cleats for my birthday yesterday, and they were already messed up. I glanced up toward the parents’ section of the bleachers. It was empty. She must be waiting for me in the comfort of her car, like all the other parents who had any sense.

Focus, Stosh, I told myself. Two outs. Runner on second. Last inning. We were down by one run. A single could tie it.

I stepped out of the batter’s box to wipe my hands and glance over at our coach, Flip Valentini, in the dugout. Flip’s a really old guy who knows more about baseball than just about anybody. He’s got arthritis and heart problems and a bum leg, but he’s still out there every day coaching us. He just loves the game. Honestly, I think it’s what keeps him going. Flip could never retire.

I got ready for the next pitch. It was armpit level, but the ump called it a strike anyway. She probably wanted to go home as much as I did. I shouldn’t be so choosy. Two and two.

“Okey-dokey!” Flip hollered at me, clapping his hands. “Fuhgetaboutit, Stosh!”

To the other team, that might have sounded like meaningless baseball chatter, but “Okey-dokey, fuhgetaboutit” is Flip’s signal for a hit-and-run play. Now Leon’s job was to run on the next pitch, and my job was to try and poke the ball through the infield.

Flip loves signs and signals. He’s constantly inventing new ones for us to memorize. He also loves stealing signs from our opponents. Nothing makes him happier than when he can let us know what the other team is about to do, and then we stop them from doing it. I think it makes him feel more like he’s part of the game.

One time I asked Flip if stealing signs was cheating, and he told me, “It ain’t cheatin’ if you don’t get caught.” According to Flip, cheating has been going on in baseball since the very beginning, when Abner Doubleday got credit for inventing the game even though he never played baseball in his life. But that’s a story for another day.

Breakowitz took off his glasses and started wiping them on his sleeve.

“Just like I taught ya, Stosh,” Flip said, clapping his hands. “Go get ’im. It’s all you, babe. All you.”

Flip and I have a long history together, in more ways than one. Once, I took him back in time with me. No, really, I did. We got a Satchel Paige baseball card and went back to 1942 with a radar gun to see if Paige could throw a fastball a hundred miles an hour. We never did answer that question, but Satch taught Flip how to throw his famous hesitation pitch. He would swing his arm around like a windmill, and it seemed like the ball would leave his hand an instant after he released it. It must have been some kind of an optical illusion or something. But it threw off a batter’s timing and was really hard to hit.

The other thing that happened while we were back in 1942 was that Flip fell for this cute waitress named Laverne. Her dad wasn’t too happy about that, and he chased us around with a shotgun. Flip and I got separated, and I had to leave him in the past. It was pretty scary.

But there was a happy ending. When I got back to the present day, Flip and Laverne were married, and Flip was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame! It turned out that he lived his adult life all over again in the past, and the hesitation pitch made him a great pitcher. He won 287 games for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Cincinnati Reds, and Pittsburgh Pirates. It just goes to show.

But that’s another story for another day, too. In the meantime, Breakowitz finished wiping off his glasses, and he was staring in for the sign.

My brain was on overload trying to remember all of the advice Flip had given me over the years. Head up. Elbows in. Bend your knees. Relax. Focus. Guard the plate. Don’t try to kill the ball. Just make contact. And of course, that old chestnut: Keep your eye on the ball.

Duh. Where else would I possibly keep my eye?

“Just meet the ball, Stosh!” Flip shouted.

TMI. Too much information. My head felt like it was about to explode.

The rain was coming down harder. At this point, I didn’t care if I got a hit or not. I just didn’t want to look bad. Anyt

hing is better than a strikeout.

I pumped my bat twice. Breakowitz went into his windup. Leon took off from second. The pitch looked hittable. So I swung.

It wasn’t any great wallop, I’ll tell you that much. I made contact, a little bit up the barrel of my bat, too close to the handle. The vibration stung my hands. But I didn’t care about that. I was digging for first.

I know we’re supposed to watch the first-base coach and not look at the ball, but I couldn’t resist. It was a little squib toward short, bouncing crazily. The shortstop had to scramble to his right to try and field the ball. It skittered past his outstretched glove, barely making it through the infield. I would be safe at first for sure and Leon was probably going to score and tie up the game. And if I could make it to second, I’d be in position to score the winning run. It would be a gamble, but maybe a gamble worth taking. I’m fairly fast, and our first-base coach, Leon’s dad, was waving me around.

“Go! Go! Go!” everybody was screaming.

I knew the base path was muddy, so I was really careful not to slip and fall making the turn around first. I jammed my right foot against the left side of the bag to get an extra little boost toward second.

The left fielder was charging in to pick up the bouncing ball. I knew he had a choice. He could throw it home to try and get Leon, or throw it to second to get me. That option made more sense, and we both knew it.

“Slide, Stosh!” somebody yelled.

I love sliding. Sometimes I slide into a base even though I don’t have to just because sliding is fun, and it looks cool, too. But I had to slide this time. I hit the dirt two strides in front of the bag and let my momentum carry me the rest of the way. The second baseman was crouched over the base, waiting for the throw.

One problem I hadn’t thought of—you slide farther on a wet field. I felt myself moving too fast in the mud, past the bag. I tried to hook my foot on it, but it was too late. Then I tried reaching back with my hand to grab the base, but the second baseman’s foot was blocking my way. He caught the ball cleanly and slapped the tag on my arm.

“Safe!” shouted the ump, who had run over to make the call. “I mean . . . out!”

That was it. The game was over.

It was my fault. I knew I was out fair and square, so I wasn’t going to argue the call. I brushed some of the mud off my pants and jogged back to the dugout with my head down. But Flip’s eyesight isn’t that good anymore, and he just about freaked out in the dugout.

“Are you out of your mind?” he screamed at the ump. “He was in there!”

Flip jumped off the bench like a wild man and charged up the three steps to get to field level. He moves pretty well for an old guy with a busted leg from a spill he took back in his playing days. But like I said, his vision isn’t so great and he must have misjudged the last step. Or maybe he just slipped.

I was crossing the third-base line when I saw it happen, almost in slow motion. I ran forward to try and grab him, but it was too late. The next thing anybody knew, Flip had fallen backward and landed hard on the concrete floor of the dugout. It all happened so fast that nobody had the chance to catch him. I just hoped he hadn’t hit his head.

Everybody came rushing over, from our team and the other team too. Nobody cared about the final score or the outcome of the game anymore. Flip was hurt. He was on his back on the floor of the dugout.

“You okay, Mr. V?” asked the ump.

“I’m fine,” Flip grunted, but it was obvious that he wasn’t fine. “My man was safe at second and you know it. You just wanted to get the game over with so you could get out of the rain.”

“Don’t move, Mr. V,” the ump told him, reaching for her cell phone. “We’re going to get you a doctor.”

“No doctors!” Flip shouted. “The last time I went to one of those quacks, it cost me four thousand bucks and Medicare wouldn’t cover it.”

“Can you get up?” one of the dads asked.

“I’ll be okay,” Flip grumbled. “Just gimme a minute.”

He lay there for a bit, and then he tried to roll over on his side. But he couldn’t do it. He groaned. You could see the pain on his face. He wasn’t going anywhere.

Somebody must have called 911 because a couple of minutes later, an ambulance pulled up in the parking lot, its siren blaring. The paramedics got out, wheeling a stretcher.

I WANTED TO VISIT FLIP IN THE HOSPITAL THE NEXT DAY, which was Sunday. I figured I’d ride my bike over after church. But my mom told me Flip had had surgery in the middle of the night and would probably be drugged up on painkillers, so I should wait a day or two. She’s a nurse at a hospital herself, so she knows about stuff like that.

It didn’t matter anyway, because I spend Sunday afternoon with my dad. He moved into an apartment on the other side of town after he and my mom split up a few years ago. We get together most weeks. My mom sort of hides upstairs when Dad comes to pick me up, so she won’t have to make chitchat with him.

“Where are we going?” I asked when Dad pulled up in his van.

“It’s a surprise,” was all he would tell me.

My dad’s van is custom-made so it can be driven without foot pedals. In fact, it doesn’t even have foot pedals. The brake and the accelerator are levers on the right side of the steering wheel. They make vans like that for handicapped people. My dad was in a car accident a while back that left him paralyzed from the waist down. That’s another story for another day. Anyway, he gets around pretty well for a guy whose legs are useless. But I help him, too. His wheelchair is in the back of the van.

We pulled up to the Louisville Marriott Hotel on West Jefferson Street, parked the van, and went inside. Dad still wouldn’t tell me what was going on, but then I saw a sign in the lobby that said BASEBALL MEMORABILIA SHOW TODAY.

I’ve been collecting cards since I was little, and my dad is the one who got me started. He’s been collecting since he was a kid, so he’s got a lot of good stuff from the sixties, seventies, and eighties—Nolan Ryan, Hank Aaron, Tom Seaver, you know. That era. I don’t usually go in for card shows myself. I’d rather add to my collection the old-fashioned way—you buy a pack of cards, peel off the wrapper, and then you get to see what goodies are inside. Is there any other product people buy where you don’t know what you’re buying? I can’t think of one. It’s just more exciting and mysterious to buy packs of cards than it is to buy cards that some dealer has on display. Cheaper, too. That’s just my opinion.

My dad has been talking a lot lately about starting a little business buying and selling sports memorabilia online, so I guess he wanted to check out the show.

“Maybe you can help me,” he said as we got on the elevator. “Hey, if this works out, you could be my partner and take over the business someday.”

I’m not really interested in becoming a memorabilia dealer, but I didn’t tell him because I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. He hasn’t had a lot of luck with jobs. Maybe this could be the break he needs.

The show was in a big ballroom at the hotel, with hundreds of tables lined up and dealers from all over the country. They were selling lots of stuff—bobblehead dolls, signed bats, balls, photos, game-worn jerseys, but mostly cards. There must have been a million baseball cards in that room. If the hotel were to catch on fire, well, a lot of people’s life savings would be wiped out pretty quickly.

We went up and down the aisles looking at stuff, and Dad stopped to chat with a few of the dealers, but he didn’t buy anything. I don’t think he was looking for anything in particular. He was just trying to get the lay of the land and see how much people were charging.

Then he rolled his wheelchair to a table with a big sign over it that said BLASTS FROM THE PAST. A guy with a scraggly beard and a Dodgers T-shirt was standing behind the table. He stuck out his hand and introduced himself as Kenny.

“What can I do you for?” Kenny asked.

“I want to get a present for my son’s birthday,” Dad said. “He just turned fourteen t

wo days ago.”

“You don’t have to buy me anything, Dad,” I told him.

I know my father doesn’t have a lot of money. He has a tough enough time paying his rent without worrying about buying me stuff that I don’t need.

Kenny told us he specializes in home runs—baseballs that were hit for home runs, photos of players hitting homers, stuff like that. He showed us what he had, but it was all either really expensive or not all that interesting. We were about to move on to the next booth, but Kenny saw he was losing a possible customer and he reached under the table. He rooted around in a box down there for a moment.

“Maybe you’d be interested in this,” he said. “I just got it in yesterday.”

He pulled out a rectangular wooden plaque with two baseball cards mounted on it, one on either side. It was dusty. The cards looked like this. . . .

Between them, inscribed on a gold plate, were the words THE SHOT HEARD ROUND THE WORLD.

Ralph Branca and Bobby Thomson. I had heard of those guys. There was a documentary on TV about them. I saw it years ago. One of them was the batter and the other was the pitcher. I didn’t remember the details.

“It was the most famous home run in baseball history,” my dad said. “Nineteen fifty-two, am I right?”

“Fifty-one,” Kenny said, wiping off the plaque with his sleeve. “Before my time.”

“Mine too,” said my dad. “The Dodgers against the Giants, right? That was the New York Giants. It was before both teams moved to California, Joey.”

“I know, Dad,” I said, rolling my eyes.

I’m not stupid. I know my baseball history. In 1958, the New York Giants became the San Francisco Giants, and the Brooklyn Dodgers became the Los Angeles Dodgers.

“The Giants won the first game of the 1951 season,” Kenny told us, “and then they lost eleven in a row. They were terrible. By August eleventh, they were thirteen and a half games behind the Dodgers. It was hopeless.”

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!