- Home

- Dan Gutman

Abner & Me Page 2

Abner & Me Read online

Page 2

Flip Valentini doesn’t have to coach our team. He does it for the fun of it. Flip doesn’t have to work at all. But he runs Flip’s Fan Club, the local baseball-card shop where a lot of us hang out. I doubt that he makes much money doing it. Coaching us and running the store is Flip’s idea of being retired. He loves baseball and always tells us he was a pretty decent pitcher in his day. Of course, that was a long time ago. He must be seventy years old now. Maybe older.

Some of the guys were complaining that Bobby Fuller had cheated, and that’s why we didn’t win the game. But the coach just put a finger to his lips to quiet them down. I knew he didn’t like complainers, so I didn’t even tell him what Fuller had done.

“Fuhgetaboutit,” Flip told us as he ran his bony hand through his white hair. “Y’know, when I was growin’ up in Brooklyn, my team was the Dodgers. ‘Dem Bums,’ we called ’em. They were a great team, like youse guys. But they lost every stinkin’ year to the Yankees in the Series. Every October it was always the same story. Wait till next year, wait till next year. But the Bums never gave up. They was always battlin’.”

“And I bet they eventually won the World Series, right, Coach?” asked our second baseman, Gabe Radley. We had all heard enough of Flip’s old baseball stories to know where he was going.

“You’re darn tootin’ they did!” Flip said. “They finally beat them Yanks in ’55 and brought Brooklyn the only Series we ever won. And then, two years later, the Dodgers said they were gonna up and leave Brooklyn. They moved to California and became the Los Angeles Dodgers. Big league baseball was gone from Brooklyn, forever. Fuhgetaboutit.”

Flip was shaking his head sadly, like the whole thing had happened yesterday.

“What’s that got to do with us, Coach?” our right fielder, Burton Ernie, asked. “Are we moving to California?”

Burton is not the brightest bulb in the box. He puts two and two together and comes up with five. Burton’s real last name is Johnson, but everybody calls him Burton Ernie because he probably still watches Sesame Street. Honestly, I can’t imagine how he made it past sixth grade.

“No, you lunkhead! The point is, youse kids should never give up neither. We’ll get ’em next time, boys. And we play these creeps again next Thursday, so be ready to battle. Next time we’ll whup them for sure. Right, Stosh?”

“Right, Coach!” I said.

Flip Valentini cracks me up. He’s pretty cool for an old guy. It’s hard to imagine him being young, but Flip told us that when he was a kid, he and his friends played a game of flipping baseball cards against a wall. Whoever flipped a card closest to the wall got to keep all the cards. That’s how he got the nickname “Flip.” We used to be called the Yellow Jackets, but then Flip decided to sponsor us. He liked owning the team so much, he decided to coach us too.

Flip also said he and his friends used to take baseball cards and stick them into the spokes of their bike wheels with clothespins so they would make a sound like a motorcycle.

Can you believe that? Throwing your baseball cards at a wall? Mangling them in your bike spokes? Man, I keep my cards in clear plastic pages that fit into loose-leaf binders. If anybody tried to stick my cards into the spokes of a bike, I’d go crazy.

Those were just different times, I guess.

I’ve been a card collector for a long time. Baseball, football, hockey, basketball. My dad got me started when I was little. That was before he and my mom split up. Dad still gives me cards sometimes. But mostly I get cards from Flip. I either buy them at his store or he hands them out after our games.

I don’t see my own dad very much, so Flip is almost like a father to me.

“Do you guys all have rides home?” Flip asked.

I usually rode my bike home after our games, but my mom had told me she was going to get off work early enough to catch the last few innings and drive me home. She still hadn’t shown up, so Flip said he’d be happy to drop me off.

Flip was one of the few people who knew my big secret. What happened was that Flip’s landlord had doubled his rent, and Flip told us he was going to have to close the store. That would have been tragic. So I got him some money.

You see, Flip had told me that Shoeless Joe Jackson’s autograph was worth half a million dollars, so I went back to 1919 and got Shoeless Joe to sign two pieces of paper for me. I gave them to Flip as a present. At first he thought the autographs were faked, but I convinced him that they were real and that I could really travel through time with baseball cards.

Flip sold one of the autographs, and that saved the store from going out of business. Flip was always nice to me, but ever since that happened, he would do anything for me.

“He grabbed ya, didn’t he?” Flip asked after I’d buckled my seat belt.

“Huh?”

“Bobby Fuller at third base,” Flip said. “He must’ve done somethin’ to stop ya from scorin’.”

“How did you know, Coach?”

“It took you about an hour to get to the plate!”

“He held on to my belt,” I admitted.

Flip threw his head back and laughed. “That Fuller kid is nuts, but I gotta admit it, he’s smart. You got to use your noodle to beat guys like that.”

It was pretty clever, come to think of it.

“So,” Flip said, “you doin’ any time travelin’ recently?”

“I’ve been playing it cool,” I said. “My mom doesn’t exactly approve. She thinks it’s too dangerous.”

“She’s right,” Flip said. “It is. She’s only lookin’ out fer ya, Stosh.”

It had been a little while since my last “trip.” I had already been looking through my baseball card collection, thinking about which player I might go visit next.

“Hey Flip,” I said as he pulled up to my house, “if you could travel through time with a baseball card and you could watch anybody in history play, who would you visit? Joe DiMaggio? Ted Williams? Roger Maris?”

Flip pulled up the emergency brake and scratched his head. “That’s a toughie,” he said. “I seen all those guys play, so it wouldn’t be such a big deal. When I was young, I saw all the greats from the 1940s and 1950s.”

He wrinkled up his forehead for a moment, and then he brightened.

“There’ve been a lotta great players over the years,” he finally said, “but there is one guy I’d really like to meet.”

“Who’s that?” I asked.

“Abner Doubleday.”

“Abner Doubleday?”

I had heard the name. I’d seen it in baseball books, and every so often I’d hear some TV announcer say something like, “Old Abner Doubleday must be turning over in his grave after that bonehead play.” But I didn’t know who he was.

“Abner Doubleday,” Flip continued, “was the guy who invented the game of baseball.

“Oh…”

“Or so they say,” Flip quickly added. “Some people say he did, and other people say he didn’t.”

“Why don’t they know for sure?” I asked.

“The story goes that Doubleday grew up in Cooperstown, New York—yeah, where the Baseball Hall of Fame is today. And one day—this is 1840 or somethin’ like that—he sketched out a baseball diamond in the dirt with a stick outside the local barber shop. He put nine players on each team, three outs, three strikes, yadda yadda yadda, and told the kids how to play this new game. But he never put it on paper and never copyrighted it or nothin’.”

“So how did anybody find out?”

“Well, that’s the thing. It wasn’t till long after Doubleday was dead that one of those kids came forward and said that was the first baseball game. Maybe he was lyin’, or maybe he was tellin’ the truth. Nobody’ll ever know for sure if Doubleday invented baseball or not. That’s who I’d like to talk to, old Abner Doubleday.”

“I could find out!” I said excitedly. “I could go back in time and find out! Maybe I could even watch baseball get invented! How cool would that be?”

Flip snorted. “O

nly one problem, Stosh,” he said. “There’s no such thing as an Abner Doubleday baseball card. They didn’t even have baseball cards back then. End of story.”

“Oh,” I said, getting out of the car. “Bummer.”

“Yeah, I guess we’ll never know who invented baseball,” Flip said. “Too bad, huh?”

“Yeah.”

“Hey Stosh,” Flip said before he pulled away from the curb. “Don’t let Fuller get you down. We’ll figure out a way to beat him next week.”

“Okay, Coach.”

4

Mom and Uncle Wilbur

WHEN I GOT HOME, I KNEW RIGHT AWAY WHY MOM hadn’t made it to my game. She was fast asleep on the couch in the living room.

My mother is a nurse in the emergency room at Louisville Hospital. That’s in Kentucky, by the way. Mom works really long and crazy hours. Sometimes she’s so exhausted at the end of the day that she just sacks out, still wearing her nurse’s uniform.

It’s hard on Mom because she has to take care of me and my great-great-uncle Wilbur too. He was sitting across from the couch in his wheelchair. Uncle Wilbur was also sleeping when I came in, but he opened his eyes when I clicked the screen door shut. He smiled at me and gave me the shush sign so I wouldn’t wake Mom.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Uncle Wilbur is alive thanks to me.

What happened was that when I went back to 1919 to meet Shoeless Joe Jackson, I also tracked down Uncle Wilbur when he was a kid. Mom had told me that he died from a disease called influenza when he was a boy. I gave him some of the flu medicine I had brought with me, and when I returned to the present day, Uncle Wilbur was alive. The medicine I gave him in 1919 saved his life. It was the most amazing thing.

Now Uncle Wilbur is really old. He doesn’t do much besides sit around and watch sports on TV.

“Did you win your game?” he whispered.

“Nah,” I said. “Tied. I hit a triple, though. I would have tagged up to score the winning run, but the third baseman grabbed my belt and held me back for a second.”

“You shoulda beat the crap outta him,” Uncle Wilbur said. “That’s what I woulda done.”

I guess I’m just not the crap-beating type.

Mom opened her eyes. When she saw me standing there in my uniform, she quickly looked at her watch and slapped her forehead.

“Joey!” she said. “I missed your game! Oh, I’m so sorry! I meant to come. I just sat down on the couch to rest for a minute and—”

“It’s okay, Mom. Coach Valentini gave me a ride home.”

“I’ll fix dinner,” she said.

“Why, is it broken?” I said to make her laugh, and I went up to my room to change clothes.

As I was peeling off my sweaty uniform, I started thinking about Abner Doubleday. It would be so cool to go back in time to meet him and find out whether or not he really invented baseball.

But how could I do it? Doubleday wasn’t a baseball player. There weren’t any cards of him. And even if he had been a player, there wouldn’t have been any cards of him. The first baseball cards, I knew, were printed in 1887. If Doubleday invented baseball around 1840 at the age of, say, twenty, then he had to be over sixty years old in 1887. Too old to play pro baseball.

Mom called me down for dinner, and I told her I would be right there.

There was another reason why there probably couldn’t be an Abner Doubleday card, it occurred to me. Baseball cards have photographs on them. It was very possible that photography hadn’t even been invented in Doubleday’s time.

As Coach Valentini says, end of story.

A photograph. An idea started to form in my head.

There used to be an old lady named Amanda Young who lived next door to us. One day she showed me an old photo she had of Honus Wagner, the Pittsburgh Pirate star. I tried to use the photo to send her back to 1909 to meet Honus Wagner. I don’t know if it worked, but I will say this—I never saw Amanda Young again. Neither did anyone else. She just vanished off the face of the earth. The Louisville police are still looking for her.

If I could send Miss Young back through time using a photograph, maybe I could use a photograph of Abner Doubleday to send myself back in time too.

That is, if a photo of Abner Doubleday even existed.

It was certainly worth a shot. There was no harm in trying.

Mom shouted that dinner was getting cold, so I washed my hands and joined her and Uncle Wilbur in the kitchen.

Mom always likes to talk about our day as we eat, no matter how boring it was. I told them about my game. Uncle Wilbur told us about some silly talk show he watches where people argue all the time and start punching each other. Mom told us that one of the patients at the hospital almost died, and they had to give her CPR. That stands for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

I didn’t mention Abner Doubleday. Even if I could find a photograph of him, there was no way Mom was going to let me go meet the guy. She never really approved of my time-travel “foolishness,” even after I saved Uncle Wilbur’s life. She thinks it’s too dangerous.

My mother is a bit of a wimp, if you ask me. She’s really tiny, not even five feet tall. I can even pick her up. She worries about every little thing. I think it’s because she’s so small that she’s easily intimidated. I would bet that if she was bigger, she wouldn’t be so overprotective of me. That’s my theory, anyway.

In fact, Mom doesn’t know the half of it. I almost got killed a few times. If I had ever let Mom know about any of the stuff that happened to me during my time travels, I’d be grounded forever.

But I just tell her the only thing that ever happens is that I get some history lessons. It’s educational, I always tell her. She loves that stuff.

Still, she’s suspicious. I’m sure that if I told her I was going to go back to the nineteenth century to ask Abner Doubleday if he really invented baseball, she’d say no.

I had some math and social studies homework to do, so I excused myself from the table and went upstairs. Most of the stuff was easy, but I had to go online to look up a few things for social studies. Some kids I knew sent me instant messages, and I shot a few back to them.

Abner Doubleday was still in my head. Just for the heck of it, I surfed over to the website for the National Baseball Hall of Fame. My dad had been to Cooperstown when he was a kid, but I’ve never been there.

I noticed there was a button that allowed you to send an e-mail to the Hall of Fame. I sat there for a long time, holding the cursor over that button. Finally, I decided to click it. This is what I typed…

Dear Sirs or Madams,

I am a 13-year-old boy who lives in Louisville, Kentucky. I have been playing baseball since I was little, and I am a big fan too. I was wondering if there exists a photograph of Abner Doubleday, and if so, do you have one and can you send it to me? I am willing to pay up to ten dollars. Any other information you might have about Abner Doubleday would be excellent.

Sincerely,

Joe Stoshack

I added my home address and hit the SEND button. A few of my instant message buddies were trying to reach me again, but before I could write back I heard my mom calling.

“What is it?” I hollered.

“Joey!” Mom yelled upstairs, “Your father is on the phone.”

5

Easy Money

MY DAD TAUGHT ME JUST ABOUT EVERYTHING I KNOW. He taught me how to play ball, of course, and all about baseball card collecting. He taught me how to fire a rifle and how to throw a Frisbee, how to play gin rummy and how to put together model cars. When I was little he taught me how to fix my bike. When I got bigger, he taught me how to jack up the car and change a flat tire.

My dad once told me that the night I was born he made a list of all the things fathers should teach their sons. He went down the list and checked off the items one by one as he accomplished them. Even after my parents got divorced, Dad would still come over every week and teach me something from his list.

&n

bsp; “Every kid needs to know how to build a campfire,” he would say. “Someday you’ll grow up and I won’t be around to do it for you.”

He won’t be teaching me much anymore, though. My dad was nearly killed in a car accident with a drunken driver. He’s lucky, actually, because he was able to gain back some movement in his upper body after a lot of therapy. He still can’t walk, though. Dad and I used to spend hours just throwing a baseball back and forth in front of our house. He can’t do that anymore, of course, and he really misses it. So do I.

Mom doesn’t usually hang around when she drops me off at Dad’s apartment. They get along okay, I suppose. But sometimes the old bad feelings come up and they start to argue.

“I’ve got something cool to show you, Butch,” he said. Dad always calls me Butch.

He waited to make sure Mom was gone and then pulled a baseball out of his pocket. It was in one of those clear plastic cases that prevents you from getting fingerprints on it.

I looked at the ball carefully, turning it around until I could see the signature on the other side…

“Wow.”

I knew a little bit about Paige. He was a star pitcher in the Negro Leagues for a long time. When the major leagues finally opened their doors to black players in the late 1940s, he was pretty old. The Cleveland Indians signed him anyway, and he could still get guys out. He was still pitching in the majors when he was about sixty years old. Now he’s in the Hall of Fame.

“How much is this worth?” I asked my dad.

“A couple of hundred,” he said. “I got it on eBay for half that.”

My dad used to be into collecting baseball cards big time. But he got tired of that hobby and sold off most of his collection so he could start collecting autographed baseballs instead.

Ever since his accident he can’t work, so he gets disability checks. They’re supposed to pay for food and rent and stuff he needs. But I think he spends a good chunk of it on the Three Bees, as he calls them—beer, blackjack, and baseballs. That’s one of the reasons he and my mom split up. She didn’t like the way Dad spent their money.

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

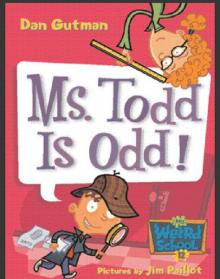

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!