- Home

- Dan Gutman

The Kid Who Ran For President Page 4

The Kid Who Ran For President Read online

Page 4

“Grown-ups have had the last one thousand years to mess up the world,” claims Moon. “Now it’s our turn.”

The young man, outfitted in a suit and tie, was raising money on Saturday by selling lemonade in front of his house for 25 cents a cup. He will have to sell 80 million cups to raise $20 million, the figure he says he needs to mount a national campaign.

Moon’s running mate and fellow lemonade saleswoman is Mrs. June Syers, a retired nurse who used to babysit for the candidate.

“We’re a perfect team,” Moon says. “I’m young and she’s old. I’m white and she’s black. I’m dumb and she’s smart.”

Watch out, Democrats and Republicans! Stand back, Tea Partiers! Here comes The Lemonade Party!

Word gets around fast. When I walked into school on Monday morning, it was like I was from another planet. Everywhere I went, everybody was looking at me, pointing, and whispering. I’d walk toward a crowd of kids and they’d part to let me through.

Pretty weird!

Abby wished me good luck. Several of the teachers gave me the thumbs-up sign. Even Chelsea came over to me.

“You weren’t kidding about running for president, were you?” she said, a lot friendlier than she was when we met.

“No, I wasn’t,” I replied. “You weren’t kidding about being First Lady, were you?”

“Actually I was,” she said. “But now that I know you’re really doing this, you can count on me.”

Arthur Krantz made a face when he saw me, and I made the same face right back at him. As every politician knows, you can’t please all the people all the time.

At first I didn’t like all the attention, but by lunchtime I had changed my mind and decided that it was kinda cool. I could definitely get used to being a celebrity.

I was signing an autograph for some third grader at my locker when Principal Berlin came over to me. I had never met the man, as it’s always been my policy to stay away from principals as much as possible. But he stuck out his hand and congratulated me.

“Mr. Moon,” he said, clapping me on the back. “You are a credit to O’Keeffe School. I wish all the students had your ambition. Listen, Judson, I was wondering if you would address the school at the assembly tomorrow morning. You can kick off your campaign right here at O’Keeffe.”

“I’m … speechless,” I stammered.

“Well, I hope you won’t be tomorrow!” he chortled. With that, he turned on his heel and ambled down the hall.

I grabbed Lane in the cafeteria.

“I’m in big trouble!” I told him. “Berlin wants me to give a speech at assembly tomorrow!”

“Great!” was Lane’s reaction.

“But the only time I ever spoke in front of a group, it was my parents. And they weren’t even listening! What am I gonna do?”

“Don’t worry!” Lane said reassuringly. “You think politicians make up their own speeches? I’ll write a dynamite speech for you. All you have to do is read it.”

“But I’m not even a good reader!” I complained.

“Relax! This is perfect. It’s a small school setting. A friendly crowd. This will give you the opportunity to get used to making speeches. Judd, every thing is going to be okay.”

That was easy for him to say. He didn’t have to stand up on the stage all by himself with three hundred and fifty kids staring at him.

I had started this whole running for president thing as a joke. But like all jokes, it was getting less funny the more I heard it.

JUDSON MOON FOR PRESIDENT read the huge banner strung across the stage. It looked like every American flag in the school had been moved into the auditorium. I peeked from behind the curtain and saw my classmates sitting out there, buzzing with excitement. The school band was playing “Hail to the Chief.” The podium looked like a lonely place to be.

Lane straightened my tie for me and handed me some sheets of paper.

“What does it say?” I asked.

“It’s a pretty standard political speech,” he replied. “You know, the flag, patriotism. Stuff like that.”

“I’m scared, Lane. What am I doing here?”

“Starting the adventure of a lifetime,” he said with a smile. “You’ll be great. Can you feel the energy out there? Feed off it! Throw their energy right back at them!”

I didn’t have any time to read Lane’s speech. Principal Berlin got up onstage. He held his hand up and made the V-sign with his fingers, which in our school means everybody has to stop talking right away.

“Students,” the principal said when everybody calmed down, “I have been at O’Keeffe School for eighteen years. In that time I have met many remarkable young men and women. But never in my years here have I run across a student with the ambition of this young man. I asked him here today to give his first public speech and kick off his campaign. I hope he will be an example to you all. Let’s give a big hand for the next president of the United States, our own … Judson Moon!”

Lane gave me a little shove and I walked to the podium.

The applause was deafening. I’ve heard applause before, of course. But never for me. When the applause is for you, it somehow sounds different. You hear the hands clapping with your ears, but it just washes over you. You can’t tell how loud it is or how long it goes on. You go into a sort of trance state.

Finally, the kids hushed themselves. The whole school was staring at me. I fumbled for the papers Lane had given me. It took all my concentration to read the words. It didn’t matter what they said. I just didn’t want to make any dumb mistakes.

“Fellow students,” I began, “we are making history today. Never, in the history of the United States of America, has a child — one of us — run for the office of president. That’s what I am doing, and I come here today to ask for your support.”

Some kids started cheering and hooting. A chant of “MOON! MOON! MOON! MOON!” swept across the auditorium. The teachers did their best to shush the kids. I waited until everybody calmed down before continuing.

“I’m sure you’re aware of the problems our country faces today. Crime. Climate change. Unemployment. Racism. Substance abuse. Too much homework …”

That got a laugh.

“Let me ask you this,” I continued. “Who is responsible for these problems? Is it Congress? Foreigners? Rich people? Poor people? Black people? White people? Women? Men? No, there is one group who is totally to blame for all the problems in our country today, and I’ll tell you who that group is.”

I paused for a moment to find my place on the page.

“Grown-ups!” I shouted.

The kids went nuts. A cheer went up. Kids were stomping their feet. The teachers began to look around at each other nervously.

“That’s who’s responsible for the problems of our country. Tell me, who’s responsible for housing discrimination, sex discrimination, and race discrimination?”

“Grown-ups!” they screamed.

“Who burned all the fossil fuels, cut down the rain forests, made our water unsafe to drink, and our air unsafe to breathe?”

“Grown-ups!” they screamed even louder.

“Who brought on the health care crisis?”

“Grown-ups!”

“Who caused every war in the history of this planet?”

“Grown-ups!”

“That’s right! Kids had nothing to do with any of these problems. Tell me this — are grown-ups going to solve all these problems they created?”

“No!” the whole school shouted.

“That’s right,” I said, more confidently. “In this young millennium, it’s gonna be up to us to solve the problems created in the last millennium. And the way I look at it, the first step is for a kid to run for president. And win!”

They were in the palm of my hand now. I could feel it. Every student was silent and staring at me, even the eighth-grade jerks who never shut up for anything. I felt like I could tell them that the earth was really flat and they’d agree with me.

/> I spotted Chelsea in the front row. She was looking at me in awe.

“Now, we all know that none of us can vote yet,” I continued. “The grown-ups made sure of that, didn’t they? What I want each of you to do is convince your parents to vote for me. You may have to beg them. You may have to put a little pressure on them. But if you want to solve these problems I’ve been talking about, do whatever you can to get your moms and dads to vote for me. Because if they vote for another grown-up, we’ll only have the same old problems grownups have caused over the last two centuries.”

“MOON! MOON! MOON! MOON! MOON! MOON!” they chanted. It took a while before I could continue.

“My fellow students, I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, ‘What’s in it for me?’ Well, I’ll tell you what’s in it for you. In appreciation for your support, my first official act as president of the United States will be to abolish homework, now and forever!”

A huge roar of approval went up across the auditorium. Clapping. Screaming. Foot stomping. The whole room was shaking. It felt like a football game. The teachers were flipping out.

I felt an exhilarating surge of power I had never experienced before. They were cheering because of me. They were whipped up because of what I was saying. It was a rush.

“If your parents vote for me,” I bellowed into the microphone, “homework will go the way of the horse and buggy.”

Fists were pumping in the air.

“Homework will become a quaint reminder of what life was like back in our parents’ childhoods!”

Kids were jumping up and down on their seats.

“In our childhood, the only place you’ll see homework will be in museums!”

It was pandemonium. I paused to allow them to calm down a little. I didn’t want to incite a riot or anything.

I noticed a boy standing in the middle of the auditorium, raising his hand and shouting insistently, “Excuse me!” Peering at him, I could see it was that jerk Arthur Krantz.

“Yes, Mr. Krantz,” I called out. “You have a comment?”

“First of all, the president of the United States has no power to abolish homework. None. Zero. Second, we need homework. Doing homework is how students reinforce what we learn at school! Homework is a good thing.”

I glanced over to Lane at the side of the stage for some advice. He was mouthing some words to me, but I couldn’t make them out. I was never any good at reading lips. But watching him gave me an idea.

“READ MY LIPS, BOOGER BOY!” I bellowed. “NO … MORE … HOMEWORK!”

“NO MORE HOMEWORK! NO MORE HOMEWORK! NO MORE HOMEWORK!” chanted the school as one. The kids around Krantz told him to shut up and sit down.

“You’re just making empty promises to get votes!” Krantz shouted at me. “Your candidacy is a joke! Your running mate is a grown-up, you hypocrite! You don’t know anything about anything. You’re going to make all kids look bad!”

A group of boys jumped on Krantz and started punching him. Some teachers rushed over to pull the boys off him. Krantz was taken out of the auditorium holding his hand over his eye.

I glanced at my speech and saw I was almost at the bottom.

“Fellow students, our grandparents had their chance to save America. They blew it! Our parents had their chance to save America. They blew it! Now it’s a new millennium and our generation is going to get our chance. Let’s not blow it! The time has come to pass the torch to a new generation. Ask not what your parents can do for you. Ask what you can do for yourselves! Kids are the only hope for America. Thank you.”

“NO MORE HOMEWORK!” the kids chanted as I left the podium. “NO MORE HOMEWORK!”

As I came off the stage, Principal Berlin looked at me like I was an insect. The teachers looked like they were in shock.

The kids, of course, looked thrilled. The dumbest guys seemed particularly happy, fist bumping me and saying stuff like, “Awesome, dude.”

“Looks as if you’ve got the kids’ vote,” Lane said, giving me a hug.

“Don’t you think that went a little too far, Lane?” I asked. “Krantz was right, you know. I can’t promise to get rid of homework! That’s crazy!”

“It’s the first rule of politics, Judd. Give the people what they want.”

Lane led me over to a guy waiting backstage. “Judson,” he said, “I want to introduce you to Ben Davis. He’s with the AP.”

“Pleased to meet you,” I said as I shook the guy’s hand. “My mom does her grocery shopping at your store.”

“Not the A&P, Judd,” Lane said, chuckling. “The A-P. Associated Press.”

“Which paper is that?” I asked.

“All of them,” Davis replied. “When I write a story, the AP puts it in hundreds of newspapers. Sometimes thousands. And we blast it out to every news web site on the net.”

“Wow!” I marveled. “And they haven’t been caught?”

He thought that was funny.

“Not every newspaper and web site creates their own content,” Davis said. “They pay a guy like me to write something once, and then they run it every where. That’s called syndication.”

“Are you going to write an article about me that will run every where?” I asked.

“You got it, kid. You’re going to be all over the news tomorrow morning.”

I gulped. Lane was beaming from ear to ear. He was taking this run for president seriously. He must have taken the clipping that appeared in the Capital Times and sent it to the Associated Press.

One day I was a fairly anonymous kid who liked to ride his bike and go fishing. The next day, virtually every man, woman, and child in America would know my name.

The instant I opened my eyes the next morning, I knew my life would never be the same.

The phone rang at 5:30. A lady asked if I was Judson Moon. When I told her I was, she said, “Judson, I’m Ann Curry with The Today Show. Could I talk with you live on the air this morning?”

“Very funny,” I said groggily, and hung up the phone. It was too early for practical jokes.

But as soon as the receiver hit the cradle, the phone rang again.

“Judson Moon?” a woman’s voice asked. “The boy who’s running for president?”

“Yes?”

“I’m Rebecca Gardner, talent coordinator with The Tonight Show. Would you be available to appear on our program tomorrow night?”

“I don’t know,” I mumbled. “I have a lot of homework this week.”

“We’ll charter a flight for you,” she offered. “First class hotel. Limousine. Would you like to visit Disneyland while you’re here? I can arrange that.”

“Can you call me back in five minutes?” I asked.

I hung up the phone and it rang again.

“Judson, this is Ann Curry again. Listen, I’m sorry I woke you up. But it’s a morning show and we have to get going pretty early …”

“Call back in five minutes!” I snapped at her.

I wanted to get Lane on the phone, but every time I put down the receiver, the phone would ring again.

Somebody from People magazine called saying they wanted to put me on the cover. The National Enquirer wanted to buy the rights to my life story. Finally I was able to speed-dial Lane.

“You gotta get over here!” I practically shouted into the phone. “America is calling!”

“The Associated Press story must have hit the papers,” he said. “I’ll be right over. Let me handle every thing.”

I hung up the phone and it rang again. It was Mrs. Syers. She complained that TMZ had woken her up at five o’clock in the morning begging to interview her.

I took the phone off the hook while waiting for Lane to bike over to my house. Mom and Dad rushed out to work before I had the chance to ask them if I could stay home from school. Lane wheeled into the driveway right after my folks pulled out of it.

The phone rang about a second after we put the receiver back on the cradle.

“Moon campaign headquarte

rs,” Lane answered matter-of-factly.

Everybody who was anybody was trying to get through. Sixty Minutes wanted me and Mrs. Syers on the show. MTV wanted to follow me around for a day with their cameras and turn my life into a reality TV show. Some Japanese TV station was willing to fly an entire camera crew to America to interview me. Ann Curry called again.

Lane cut a deal with a big New York publisher for my life story. He told Pepsi I don’t do commercial endorsements. Watching Lane work the phone was like watching a master potter mold a vase out of clay.

When the smoke had cleared, Mrs. Syers and I were scheduled to appear on The Today Show, The Tonight Show, The Late Show, The Daily Show, and Good Morning America. I would be on the cover of People, Sports Illustrated for Kids, Time, and Boys’ Life.

Hardball wanted me to go on their show, but only if I didn’t appear on any other TV shows. Lane told them to buzz off. He turned down requests from the TV shows, magazines, and bloggers he never heard of.

“Why did you turn down Meet the Press?” I asked Lane. “I thought that was your favorite show.”

“You’re not ready to meet the press,” he replied.

In the middle of all this, I managed to get through to school and tell them I wouldn’t be coming in. I told the secretary I had a funny feeling in the pit of my stomach, which was absolutely true. She had read the papers, and said she thought everybody would understand.

By ten o’clock, reporters started gathering out on the front lawn, setting up cameras and satellite hookups. Some guy was trying to interview me with a bullhorn. I pulled the shades down. It was like Night of the Living Dead, when the zombies are trying to claw their way into the house.

We decided to let just one reporter in — Pete Guerra, the guy who came out to the lemonade stand and wrote the first story about my run for the presidency.

“The power of the press,” muttered Guerra after pushing his way through the mob of reporters and through the front door. “You’re gonna have to reseed your lawn, Moon. Reporters are worse than animals.”

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

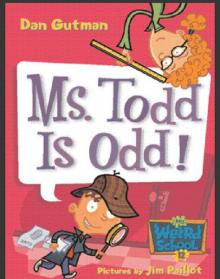

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!