- Home

- Dan Gutman

The Kid Who Became President Page 9

The Kid Who Became President Read online

Page 9

And then something incredible happened.

Front page of the Washington Post, November 18:

POPULARITY AT ALL-TIME LOW,

MOON FIRES CHIEF OF STAFF

November 23 started out like most other days. I was being given a gift at the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington. Every year, just before Thanksgiving, the president is presented with a turkey.

They always pick a big turkey, because it shows up well in photos, which appear in lots of newspapers on Thanksgiving Day. This turkey was enormous — fifty-eight pounds. The thing was way too big for anybody to eat. After the photographers were done, I was told, I would receive a regular turkey and they’d send the big one back to the farm where it came from.

“Keep an eye on that turkey,” I instructed Secret Service Agent Doe when the turkey was led away. “It looks like it might have a bomb inside it.”

“Yes, sir,” he replied. I had been trying to make Doe laugh ever since I became president, but so far I had been unsuccessful.

As we left the hotel I was surrounded, as always, by Secret Service agents. Agent Doe was in the front, while eight or nine other agents walked by my side and behind me.

My limousine was parked on the street by the side entrance to the hotel. The Secret Service doesn’t like to pull up to a front entrance because too many people gather around to catch a glimpse of me and it can be difficult to control the crowd.

The limo was about fifteen feet from the door. As I walked out the door, I could see some reporters and photographers gathered behind a rope, along with a few curious passersby. I waved to them and shouted greetings.

I was about halfway to the limo when I heard a popping sound.

Pop … poppop. Pop. It sounded like those little firecrackers my friends and I used to set off on the Fourth of July. There was a burst of about five or six pops. For a moment the thought crossed my mind that Thanksgiving was an odd time to be setting off fireworks.

I was still waving to the crowd when Agent Doe stumbled in front of me and then tumbled to the sidewalk.

“Are you okay?” I started to ask him. I bent down to see what was wrong, but suddenly one of the other Secret Service agents grabbed me from behind and threw his body over me.

“Hey, get off!” I yelled.

“Get the president out of here!” somebody yelled. “Get him out!”

There was wild confusion after that. People started screaming and running around. Agent Doe was writhing on the sidewalk. There was a red splotch on his white shirt.

Somebody picked me up, threw me into the limo, and jumped on top of me. I made sure I still had the football. There was a siren. And just a few seconds after I first heard the popping sound, the tires screeched and the limo sped off.

“George Washington University Hospital,” one of the Secret Service agents barked to the driver.

“What’s going on?” I asked when the other agent got off me.

“Somebody tried to shoot you, sir.”

“I think Agent Doe might have been hit!” I yelled. “We’ve got to go back and get him!”

“No, sir,” one of the agents told me. “Our job is to protect you.”

I didn’t think I was hit. They searched me for bullet holes. They didn’t find any but insisted on taking me to the hospital just to be on the safe side. If it hadn’t been for Agent Doe walking in front of me, I realized, that would have been me bleeding on the sidewalk.

On the way to the hospital, we got word by cell phone that a man had been arrested. He had a history of mental problems and had managed to get a gun and position himself with the group of reporters who were waiting for me as I came out of the hotel.

“What about Agent Doe?” I shouted.

“They’re rushing him to George Washington University Hospital,” was the response.

We were at the hospital in minutes. I ran ahead of the Secret Service agents and rushed through the automatic doors of the emergency room. The guard told me the ambulance hadn’t arrived yet.

“His name is John Doe!” I shouted to the lady at the admissions desk. “And that’s his real name! He’s a big guy. Black. Bald. You’ve got to save his life!”

A few seconds later, the ambulance pulled up, sirens blaring. Two paramedics dashed outside and began to unload the stretcher. They struggled to carry Agent Doe’s enormous body, so my Secret Service agents and I ran over to help. There was blood all over Doe’s shirt now.

“Hang on!” I yelled at him as we rolled him inside. “Don’t die on me.”

Agent Doe didn’t respond. His eyes were closed. I couldn’t tell whether or not he was breathing.

I held the handrail of the gurney as we pushed it down the corridor. I kept saying encouraging things, but Agent Doe wasn’t responding. We came to a set of big double doors.

“We’ll take it from here, Mr. President,” a nurse said.

“But I want to be with him,” I protested.

“I’m sorry, sir,” she told me. “You’re not allowed in the operating room.”

I sat in the waiting room with the Secret Service agents for the next three hours. Every so often I’d get up and ask a nurse if she had any information about Agent Doe. All she could tell me was that she would let me know as soon as she got a report.

I skimmed a magazine, but I couldn’t pay attention to the words. I kept thinking about Agent Doe.

Finally, a doctor came out and walked straight toward me. I was prepared for the worst.

“Agent Doe is alive,” he said.

I let out a big sigh of relief. “Is he going to be okay?” I asked.

“He took a pretty good hit, sir,” the doctor continued. “The human body has five to six quarts of blood in it, and he’s lost quite a bit. We’re replacing it, and he’s in stable condition. There’s no blood in his stomach, which is good.”

“Where was he hit?” I asked.

“We found three .22 caliber bullets in him. None of them hit his heart, but one entered below his left arm, traveled down about three inches, struck his seventh rib, and lodged itself in his lung. There is no exit wound.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means the bullet is still inside him. But that’s okay. Lots of people live their whole lives with bullets in them. He’s a big fellow. I think he’s going to make it, sir.”

The last time I cried, I was in third grade. We had planted some seeds in paper cups, and mine was the only one that didn’t grow. The other kids in the class made so much fun of me for crying that I resolved never to let anyone see me cry again.

But I was so sad that Agent Doe had been shot, and so happy that he was still alive, that I couldn’t hold back my tears.

Later, Agent Doe was wheeled out to the recovery room and I got to see him. There were tubes going in and out of different parts of his body and a clear plastic mask was over his nose and mouth. Plastic bags filled with liquid hung over his bed. He was hooked up to some machines, I guess to help him breathe.

I had always thought of Agent Doe as a big, tough guy. But now, lying there helplessly in a green surgical gown, he looked so weak. It’s amazing what a tiny bullet can do to a human body. I took his huge hand in mine.

Agent Doe’s eyes were shut when he was wheeled into the recovery room, but soon the drugs wore off and his eyelids flickered open. He couldn’t speak because of all the tubes. He saw me and signaled with his hands that he wanted to write something on a piece of paper. The doctor indicated it was okay, and I handed Doe a pad and pencil.

R U OK? he wrote, grimacing with pain.

“I’m fine,” I replied. “How about you?”

BEEN BETTER.

“Now we’re even,” I told him. “I saved your life when you were in the pool, and you saved mine today.”

JUST DOING MY JOB, he wrote.

A nurse came into the room. He was holding a special afternoon edition of the Washington Post, and he held it up for Agent Doe to see the headline:

SECRET SERVIC

E AGENT IS HERO,

TAKES BULLETS AIMED AT MOON

Next to the story of the shooting was the usual approval rating nonsense:

“Wow,” I said, “I haven’t been this popular since the inauguration.”

U SHOULD GET SHOT AT EVERY DAY, Agent Doe wrote on his pad.

“Is that a joke?” I asked him. “Did you actually tell a joke? I can’t believe it!” I started yelling to all who could hear, “Agent Doe told a joke! Alert the media! Stop the presses! This should be front page news! Declare a national holiday!”

STOP IT, he wrote. HURTS TO LAUGH.

“You’re laughing?!”

I grabbed my chest and pretended to fall down in a dead faint.

“Agent Doe is actually laughing!” I hollered to the nurses. “I can’t believe it. Somebody get a camera! I need to get this on video to preserve for future generations! Nobody will ever believe it.”

STOP! he wrote again, underlining the word.

With all those tubes going in and out of him, I can’t say for sure that Agent Doe was laughing. But his body was shaking, he had a big smile on his face, and tears were sliding down his cheeks. That was good enough for me.

The worst crisis of my presidency was over. Or so I thought.

Every year, a tree is chosen to be the national Christmas tree. It is brought to Washington and displayed on the White House lawn. This year’s tree was a huge evergreen that grew in Pennsylvania. It was a beautiful thing, decorated with ornaments made by children from all the fifty states.

I got to ride a cherry picker to place a star on the top of the tree. Then I flicked the switch that turned on the lights. The whole world seemed to brighten. A choir sang Christmas carols until midnight. Just as they launched into “White Christmas,” snow began to fall. It was a magical evening.

My first year in office was almost over. In a few weeks, I would be giving the annual State of the Union Address. I certainly hadn’t been the best president in American history, but I hadn’t been the worst, either. My approval rating was very high after the assassination attempt. I was a survivor, in more ways than one. Things had gone pretty well, all in all.

On Christmas Eve, I went to bed thinking about the presents my parents were going to give me in the morning. I had my eye on a new video game system and hoped I’d dropped enough hints so they would buy it for me.

I was in the middle of a deep sleep when I felt someone shaking me.

“Santa?” I grunted hopefully. “Is that you?”

“Mr. President, wake up, sir. It’s important.”

It was Honeywell. He was with Vice President Syers.

“Too early,” I muttered. “Leave me alone.”

“President Moon,” Vice President Syers said urgently, “there are troops on the border of Cantania, and they look like they’re going to invade Boraguay. You’ve got to get up right away.”

“Just nuke them,” I said groggily, “and let me go back to sleep.”

“This is a national emergency!” Vice President Syers said as she pulled off my covers. “Get up!”

I rubbed the sleep from my eyes, throwing on a bathrobe and my fuzzy slippers. The clock next to my bed said it was two in the morning. I accompanied Vice President Syers down to the Map Room in the basement of the White House. Some men in military uniform were seated around the long table — the secretary of defense, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Brigadier General Herbert Dunn, and Colonel Dwaine Cooper of the Air Force.

I hadn’t had the chance to spend much time with the leaders of the armed forces during my first eleven months as president. But when I walked into the room, they all snapped to attention and saluted.

“What’s up?” I asked, returning their salutes.

“Mr. President,” the secretary of defense said, “our spy satellites have detected — and we have photographic proof — that in South America, the Cantanian army is massing at the border of Boraguay. We believe an invasion will come within the next twenty-four hours.”

“Why is that our business?” I asked. “If two countries want to fight, why should we stop them?”

“Because Boraguay is one of the biggest oil-producing nations in the world, sir. Their government is friendly to the United States. If Cantania takes over the oil fields, the United States will be at the mercy of Supreme Ruler Raul Trujillo, the dictator who runs Cantania.”

“Trujillo … Trujillo …” I mumbled. “How do I know that name?”

“He was at your first state dinner,” Vice President Syers reminded me.

“Oh yeah,” I recalled. “The friendly dictator. He seemed drunk or something.”

“He’s drunk with power,” the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said. “We’ve got to stop him, sir.”

“What do you suggest we do?” I asked.

“I say we attack now,” General Dunn said, pounding the table. “Bomb them back to the Stone Age. Teach ’em a lesson.”

“Yes, and start World War III!” snorted Colonel Cooper. “We have to be very cautious, sir. I suggest we cut off all relations with Cantania immediately.”

“That makes us look weak!” General Dunn insisted. “We’ve got to let Trujillo know we’ll use our military might if we have to.”

“We could blockade them,” the secretary of defense said. “That’s what Kennedy did to end the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. We could cut off all food and supplies entering Cantania.”

“It’s too late for that,” commented Vice President Syers.

“Why not consult Congress?” I suggested. “Let them debate the issue and then make a decision.”

“There’s no time, sir! Trujillo will have the manpower and supplies to launch an attack by late tomorrow.”

“If we bomb them, we don’t have to call it a war, you know,” General Dunn said. “Call it a police action. That’s what Truman did in Korea in 1950. We never officially declared war in Vietnam, Iraq, or Afghanistan, either.”

The four of them discussed all the options the United States could take. When they were done, they all looked at me.

The final decision, I realized, was mine. These military leaders couldn’t make this decision for me. Congress couldn’t make this decision for me. My parents couldn’t make this decision for me.

When I first became president, I had complained that the president didn’t have the power to do much. But now I was facing a situation in which I had enormous power. My decision would affect the course of world history. It was terrifying.

As I sat there with all their eyes trained on me, I felt like saying, “What are you guys looking at me for? I’m just a kid.”

“How long do I have to reach a decision?” I asked the group.

“We need to send a clear message to Trujillo first thing in the morning, sir,” said the secretary of defense.

“Gentlemen,” I said, saluting them, “then I’ll see you here first thing in the morning.”

I pushed Vice President Syers’s wheelchair out of the Map Room. Honeywell said he would escort her home. “Some Christmas present, huh?” Vice President Syers said as she rolled down the ramp to her car.

Going back to sleep was out of the question. I had just been informed that I had five hours to make a decision that could plunge the United States into a foreign war. How could I sleep?

A long hallway runs the entire length of the second floor of the White House. All was quiet as I paced back and forth in my bathrobe and fuzzy slippers. Mom and Dad’s room was silent. So was Chelsea’s room and her parents’ room. The Secret Service agents were out of sight. Honeywell hadn’t returned yet from driving Vice President Syers home. For once, I had the whole White House to myself.

And then I heard a noise.

It sounded like a bed creaking, or maybe a floorboard. I turned. There it was again! It was coming from the Lincoln Bedroom. My dad must be working late, I figured, filling orders for the White House Box and Carpet Tile Company.

I opened the door gently and l

et out a gasp. There, sitting calmly on the bed, was Abraham Lincoln.

It couldn’t be the real Abraham Lincoln, I knew. Lincoln was cut down by an assassin’s bullet in 1865. It had to be his ghost. Honeywell told me the ghost of Abraham Lincoln had been spotted in the White House, and I had living proof of it. Well, proof of it, anyway. The ghost looked more like a hologram than a live person.

When I opened the door, Lincoln turned his head and looked at me. He didn’t look exactly like the Abraham Lincoln on a five-dollar bill. He appeared younger. There were fewer lines in his face. Death had been good to him.

“It is time we met,” Lincoln said softly. “The Union is in crisis. It is the eternal struggle between these two principles — right and wrong. They are the two principles that have stood face to face from the beginning of time and will ever continue to struggle.”

“Y-yes,” I croaked. “Sorry about all the boxes and stuff. This is my dad’s home office. He didn’t know you would —”

“Never mind that,” Lincoln interrupted. “What course of action do you intend to take?” Clearly, Lincoln was not in the mood for chitchat.

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “I’ve always done what people told me to do. I’m just a boy.”

“Now you must lead, as a man,” Lincoln said. “The presidency is like a suit. Many try it on. Sometimes it fits. Sometimes not. And sometimes … one grows into it. I was a simple country lawyer before I tried on that suit. I had to grow into it. So must you.”

“I’m prepared to lead,” I said, “but I don’t want to lead America to war.”

“Neither did I,” Lincoln said sadly. “War came to me. I could not escape it. Perhaps you can.”

“How?”

“That I do not know,” Lincoln sighed. “But I beg you to remember this. The government should not use force unless force is used against it. In a choice of evils, war may not always be the worst. Still, I would do all in my power to avert it. As commander in chief, you have the right to take any measure that will preserve the Union, subdue an enemy, and ultimately bring peace. I was successful in achieving those goals. But the price — six hundred thousand lives — was enormous. I pray the mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. I must take my leave.”

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

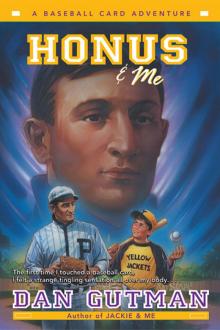

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

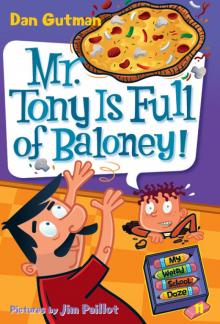

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

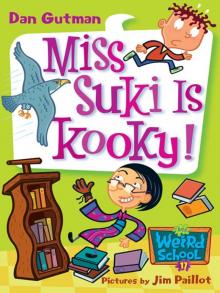

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

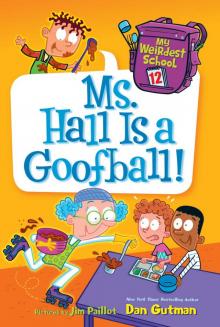

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

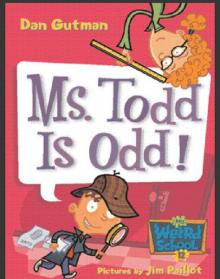

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!