- Home

- Dan Gutman

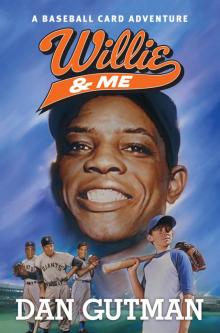

Willie & Me Page 9

Willie & Me Read online

Page 9

Think. Think. What am I going to do when I get to 1951? What can I do to change things back to the way they were?

I looked around my bedroom. My eyes fell upon the small box at the edge of my desk. The little video camera that my grandmother had given me for my birthday was in there.

Of course!

I opened the box and slipped the little camera in my pocket. Then I picked up the Bobby Thomson card. It was my ticket to 1951. I closed my eyes and tried to get in the mood. It wasn’t easy. I had a lot on my mind. This was going to be a mission that I had to complete. I couldn’t mess up this time. If I failed, Willie Mays would be a failure. And I would never be able to forgive myself.

It took a while—longer than usual. There were no tingles in my fingertips. No nothing.

I was getting impatient. Maybe I had damaged the Thomson card when I cut it off the plaque. Maybe I had lost my power to travel through time. I had always worried that as I grew older, one day my power would be gone—like when a boy’s voice changes around my age.

Maybe I was just pressing, like a batter who’s trying too hard to get a hit, and he can’t hit anything. Or maybe I was only able to travel back to the same year once. Who knows what could have gone wrong?

But then, when I was just about to give up, something happened. I started to feel that old familiar tingling sensation in the tips of my fingers.

It was happening, and it happened fast this time. I was buzzing all over. I felt lightheaded and dizzy. I really should have had something to eat. But no time for that. Atom by atom, my body was deconstructing in the present day and reassembling itself in the past. It was the strangest feeling.

“Joey, is everything okay in there?” my mother asked.

And then I felt myself vanish.

THIS TIME—FOR A CHANGE—I LANDED EXACTLY WHERE I wanted to be and when I wanted to be there. I was right outside the Polo Grounds. Perfect. It was early in the day, just as I’d hoped. The place looked deserted. I ran over to the same chain-link fence I’d scaled the first time, and dug a toe into it. So far, so good.

“Hey, you!” somebody yelled.

Uh-oh.

I stopped and turned around slowly.

There was a cop standing there. Or maybe he was a security guard. He was wearing a uniform, but he didn’t have a gun on his belt. Just some kind of a billy club. His arms were folded across his chest.

“Whaddaya think you doin’ here?” he asked gruffly.

“Nothing.”

“It’s Wednesday. Why ain’t you in school?” he said.

“I . . . I . . .” I had nothing to say.

“Don’t you know that trespassin’ is against the law?” the guy said. “I should turn you in.”

Oh no. Not again. This could not be a good thing.

On second thought, maybe it could be a good thing. I hopped down off the fence and stuck out my hand like he and I were old friends. He didn’t shake it.

“I need to talk to Leo Durocher,” I said, trying to sound confident. “It’s very important. A matter of life and death, really.”

The guy looked at me for a long time, as if he was trying to figure me out. He fingered his billy club, like he was looking for a reason to use it. I wasn’t about to make any sudden moves.

“Talk to Mr. Durocher about what?” he asked.

“I have something that he needs,” I said.

I didn’t want to tell this security guard any more than he needed to know.

“Mr. Durocher ain’t here yet,” he said. “The game don’t start for hours. If you have somethin’ to give ’im, give it to me and I’ll pass it along.”

I wasn’t sure if I could trust the guy. But I didn’t have a whole lot of choices. Maybe I could try dazzling him, I figured. I pulled my little video camera out of my pocket.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“It’s a camera.”

“That ain’t no camera,” he replied, laughing. “That thing’s too little to be a camera. There’s no place to put the film.”

“It doesn’t use film,” I said, pushing the power button. “Look.”

The screen lit up. I pointed the camera across the street from the ballpark, so he could see the view with his own eyes and also see it on the screen at the same time.

The security guard’s mouth dropped open.

I knew that digital cameras came along sometime in the 1980s. Before then, cameras recorded their images on film, not computer chips. One time, my uncle Wilbur showed me an old film camera that he keeps on his bookshelf. With film, you didn’t see what you were shooting on a screen—you looked through what they called a “viewfinder.” It was just a little window in the camera.

You couldn’t see your picture instantly, either. You had to send the film out to a lab to be “developed.” And you couldn’t shoot movies with a regular camera in those days. You had to have two separate devices to shoot movies and still pictures. This security guy had never seen anything like my camera.

I shot a selfie with him in it, and then held the camera up so he could see the picture on the screen.

“Holy smokes!” he exclaimed. “Where’d you get that thing?”

“It was a present from my grandmother,” I said honestly. “Watch this. It’s called zoom.”

I pushed the button that enlarges the image. His jaw dropped open again as he watched the picture of himself get bigger and bigger until the screen was filled with just his eyes and nose.

It was like I had dangled shiny beads in front of a tribe of primitive people. The guy no longer had any interest in hitting me with his club or turning me in. His eyes were wide.

“Is that magic?” he asked.

“No, it’s digital,” I replied, knowing he wouldn’t understand. “Look, I need you to do something very important. I need you to give this camera to Leo Durocher.”

“Why?”

“He’ll know what to do with it,” I said. “But it’s really important that you show him how to do the zoom thing with this button. Can you do that for me?”

“Yeah, I guess so. Okay.”

To make sure he understood, I showed him how to turn the camera on and use the zoom button again.

It was a long shot, I knew. But I had a hunch that as soon as Leo Durocher saw what my camera could do, the first thing he would think of was how he could use it to cheat. And zooming in with my video camera would serve the exact same purpose as using a telescope to steal signs. I felt bad about giving away the camera my grandmother had given me as a present, but this was a matter of life and death.

“Thank you,” I said to the security guard.

There was no reason for me to stick around. I ran across the street and ducked into an alley between two buildings. I pulled out a new baseball card, sat down on the ground, and closed my eyes.

Home, I thought. I just want to go home and stay there. I will never do this again. It’s too risky.

It didn’t take long for the tingling sensation to come and take me away. This time, I didn’t go flying across the living room. I went flying across the kitchen. Narrowly missing the kitchen table, I swerved to avoid going headfirst into the refrigerator, and almost knocked the little TV off its stand.

Uncle Wilbur was sitting there. Mom was standing at the stove.

“You’re just in time,” she said, almost matter-of-factly. She was getting used to my comings and goings. “We’re having chicken.”

“Did you guys ever hear of Willie Mays?” I asked as I was getting up.

“Of course we’ve heard of Willie Mays,” my mother said. “Why?”

“I told you the boy is loco,” said Uncle Wilbur.

“Are you feeling okay, Joey?” my mother asked as she put her hand on my forehead.

I wasn’t convinced.

“Who was he?” I asked. “Who was Willie Mays?”

“He was a baseball player,” my mother replied. “Everybody knows that.”

“He played for the Giants,” added Uncle

Wilbur. “Superstar. One of the best ever.”

I had to be sure. I ran upstairs and woke up my computer. It didn’t take a lot of searching online to confirm that everything checked out. The Giants won the 1951 pennant. Thomson hit the Shot Heard Round the World, and was the hero. Branca was the goat. Willie Mays was on deck when the game ended, and he went on to a long, successful Hall of Fame career. There is even a large statue of him in front of the ballpark where the Giants play today.

“Yes!”

The security guard did give my camera to Leo Durocher! The Giants used it to steal the signs. It had worked like a charm. History had been changed back again.

I let out a tremendous sigh of relief. I had messed things up terribly, but I was able to go back and fix them. A feeling of happiness . . . giddiness . . . came over me. I came running down the stairs.

“I did it!” I announced. “I, Joe Stoshack, singlehandedly saved Willie Mays’s life!”

“Good,” said my mom. “Come eat. It’s getting cold.”

“The boy is loco,” said Uncle Wilbur.

While we were eating, my mom’s cell phone rang. She doesn’t like to take calls during dinner, but every so often there’s an emergency so she always checks to see who’s calling. She took the phone into the living room and had a short, whispered conversation with somebody.

“That was Laverne Valentini,” she said when she came back. “Flip isn’t doing well. We’d better get over to the hospital.”

I grabbed a piece of chicken and ran out the door.

ON THE WAY TO THE HOSPITAL, MY MOTHER WAS DRIVING faster than she usually does. I hoped she wouldn’t get pulled over by the police.

When we got to Flip’s room, Laverne was sitting in a chair next to the bed, holding Flip’s hand. His eyes were closed. The lights were dim. A doctor and nurse were looking at monitors that were hooked up to Flip. He had tubes running into his nose and an IV in his arm. At his bedside I noticed a book titled Physics of the Impossible.

“How is he?” my mother whispered.

“We’re doing all we can for him,” replied the doctor without looking up.

“He is what he is,” said Laverne.

Flip seemed agitated. His eyes were closed, but he was gesturing with his hands.

“These physicists in Italy say they’ve seen subatomic neutrinos travelin’ faster than the speed of light,” Flip mumbled to nobody in particular. “So it’s possible to go back in time. The flux capacitor can reverse the polarity of the wormhole.”

“Shhh,” Laverne leaned over to whisper in Flip’s ear. “Everything’s okay, honey.”

Flip started ranting something about vacuum chambers, fiber optics, and semitransparent beam splitters. He wasn’t making any sense.

“It’s the drugs,” the nurse told us. “They make him delirious.”

“Think about it,” Flip mumbled. “In just one second, a cheetah can run thirty-four yards. A telephone signal can travel 100,000 miles. A hummingbird can beat its wings seventy times. Eight million blood cells can die. . . .”

“Try to rest, Mr. Valentini,” said the nurse.

I wanted to tell Flip about my adventure going back and forth to save Willie Mays, but it didn’t seem like the right time or place.

Suddenly, Flip stopped ranting. He opened his eyes and looked up at me.

“Stosh . . .”

“Yeah, it’s me, Flip,” I said. I leaned over the bed and took his hand.

“We gotta get to the game, Stosh!” he said urgently. “We’re gonna be late.”

“There’s no game, Flip,” I told him. “Don’t worry about that.”

“No game?”

He looked up at me. His eyes were clear. I shook my head.

“No game,” I said.

Flip nodded slightly and took a deep breath. Then he closed his eyes.

A second later, beeping noises came out of the monitors that were hooked up to Flip. The doctor and nurse started frantically pressing on Flip’s chest, blowing air into his mouth, and giving him shots. A few more doctors came running in and started working on him.

“What’s happening?” I asked.

“You folks need to leave,” one of the doctors said. But we weren’t going anywhere.

Flip wasn’t responding. His chest wasn’t moving up and down. He wasn’t breathing. The monitors were still beeping. Laverne and my mom started crying.

After a few intense minutes, the first doctor stepped away from the bed and pulled off his rubber gloves.

“That’s it,” he said, looking at his watch and then at Laverne. “I’m sorry, ma’am. We did what we could.”

I never really appreciated how famous Flip was until he died. His name was all over the news that night, and there were stories about him in the papers and online, too. Our phone rang off the hook.

Flip’s funeral was held a few days later. I wore my nice jacket and tie and we went to this fancy funeral parlor on Taylorsville Road in Louisville. The place was filled with flowers. Hundreds of people had come from all over the country. Some of them were famous baseball players. Some of them were just fans. All the players on my team were there, of course. Some of their parents came, too. My dad showed up. Flip was so loved by so many people.

It was a really nice ceremony. Everybody was sniffling and sobbing and handing out tissues while they swapped stories about Flip. A bunch of people got up to talk. Before the funeral, Laverne had asked me if I wanted to say a few words. After all, I had played a pretty big part in Flip’s life.

But what was I going to do—get up there and tell everybody that Flip and I traveled back in time together? I couldn’t say that I left him in 1942, and that’s when he met Laverne and learned how to throw the hesitation pitch from Satchel Paige. Nobody would believe it. They would think I was being disrespectful, or just plain crazy. I probably would have been thrown out of the funeral parlor.

It didn’t matter. I wouldn’t have been able to make it past the first sentence anyway. I’m not all that emotional, myself. But every time somebody said something about Flip, I would get this lump in my throat and I had to fight back tears.

When the funeral was over and people started to say their good-byes and head for their cars, Laverne put her arm around me and told me she wanted to speak with me privately. There were some dark, streaky lines on her face from the tears that had mixed with her makeup. I went with her to a little room behind the chapel.

“I wanted to thank you again, Stosh,” she told me, holding my hand. “If it hadn’t been for you, I never would have met Flip in the first place. I shudder to think what my life would have been like if he hadn’t come into it. We had so many wonderful years together.”

“You’re welcome,” I said awkwardly.

I didn’t know what else to say. When somebody says “thank you,” it seems like you should say “you’re welcome.” But it just sounded a little bit strange in this situation.

“Oh, one more thing,” Laverne said, as she opened a closet door and pulled out a long, thin box that was wrapped in red paper. “This is for you. Think of it as another birthday present.”

What could she possibly be giving me? The box was about the size of a skateboard. But why would Flip’s wife be giving me a skateboard? I’d never expressed any interest in skateboarding.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Flip had been talking about liquidating the inventory of the store for a long time,” Laverne told me. “So before he went into the hospital, he had this made. He told me he wanted you to have it.”

I tore off the wrapping paper and opened the box. I was relieved that it wasn’t a skateboard. It was a wooden plaque, very much like the one my father had given me for my birthday, but longer. Instead of two baseball cards mounted on it, there were ten.

Honus Wagner. Jackie Robinson. Babe Ruth. Shoeless Joe Jackson. Satchel Paige. Ray Chapman. Jim Thorpe. Roberto Clemente. Ted Williams. They were all in a line. And the last card on the right was Flip, in his Bro

oklyn Dodgers uniform.

That’s when I lost it. During the funeral, I had come close to crying a few times, but I managed to hold it in. There was no stopping it now. I was blubbering like a baby. Laverne held me and we cried together.

THE PLAQUE WITH ALL THOSE BASEBALL CARDS ON IT WAS the nicest gift anyone had ever given to me. It was definitely worth a lot of money, and the smart thing to do would be to lock it up in a safe somewhere.

But that didn’t seem right. I decided that I was going to put it up on the wall of my bedroom, right above my desk so I could look at it for inspiration while I was doing my homework and stuff. Maybe we could get an alarm system or something to prevent anyone from breaking into the house and stealing it.

The day after Flip’s funeral, I decided for sure that it was time to announce my “retirement.” I wasn’t going to travel through time anymore.

It had been fun, and I’d had some amazing experiences. But I decided that going back in time was simply too dangerous. I had been kidnapped, shot at, attacked, and nearly killed on numerous occasions. If anything ever happened to me and I didn’t make it back to the present day, I don’t know if my mom could handle it.

And after what happened with Willie Mays, I finally realized how powerful the butterfly effect could be. It was way too easy for me to change some little thing in the past that would have a dramatic impact on the future.

At least now, I had this beautiful plaque so I could think back about the trips I had been on, and to remind me of Flip.

I remembered the time I had dinner with Babe Ruth in New York City. Man, that guy could eat. He got sick and threw up all over the place.

I remembered going fishing with Ted Williams, hunting with Satchel Paige, and meeting Lou Gehrig on a train to Chicago.

I remembered the batting lesson I got from the great Honus Wagner.

I remembered the time I went to bed wishing I could experience what Jackie Robinson experienced when he broke the color barrier. And when I woke up, I was an African-American kid in 1947.

My Weirder-est School #3

My Weirder-est School #3 Bummer in the Summer!

Bummer in the Summer! Flashback Four #4

Flashback Four #4 Miss Blake Is a Flake!

Miss Blake Is a Flake! My Weirder-est School #2

My Weirder-est School #2 My Weirder-est School #1

My Weirder-est School #1 Miss Aker Is a Maker!

Miss Aker Is a Maker! Houdini and Me

Houdini and Me Mr. Marty Loves a Party!

Mr. Marty Loves a Party! Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo!

Ms. Jo-Jo Is a Yo-Yo! Jackie & Me

Jackie & Me Miss Newman Isn't Human!

Miss Newman Isn't Human! Miss Mary Is Scary!

Miss Mary Is Scary! Miss Laney Is Zany!

Miss Laney Is Zany! Miss Tracy Is Spacey!

Miss Tracy Is Spacey! Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up!

Ms. Krup Cracks Me Up! Mrs. Cooney Is Loony!

Mrs. Cooney Is Loony! Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous!

Dr. Nicholas Is Ridiculous! My Weird School Special

My Weird School Special The Titanic Mission

The Titanic Mission Ted & Me

Ted & Me Jim & Me

Jim & Me Miss Child Has Gone Wild!

Miss Child Has Gone Wild! The Talent Show

The Talent Show Mickey & Me

Mickey & Me Return of the Homework Machine

Return of the Homework Machine The Lincoln Project

The Lincoln Project Ray & Me

Ray & Me We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do?

We're Red, Weird, and Blue! What Can We Do? The Get Rich Quick Club

The Get Rich Quick Club Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang

Funny Boy Versus the Bubble-Brained Barbers from the Big Bang Never Say Genius

Never Say Genius Miss Brown Is Upside Down!

Miss Brown Is Upside Down! Coach Hyatt Is a Riot!

Coach Hyatt Is a Riot! The Christmas Genie

The Christmas Genie Mr. Burke Is Berserk!

Mr. Burke Is Berserk! Mr. Louie Is Screwy!

Mr. Louie Is Screwy! Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy!

Mrs. Roopy Is Loopy! Ms. Sue Has No Clue!

Ms. Sue Has No Clue! Satch & Me

Satch & Me Mr. Cooper Is Super!

Mr. Cooper Is Super! Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds!

Oh, Valentine, We've Lost Our Minds! Miss Small Is off the Wall!

Miss Small Is off the Wall! Ms. LaGrange Is Strange!

Ms. LaGrange Is Strange! Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay)

Funny Boy Meets the Dumbbell Dentist from Deimos (with Dangerous Dental Decay) Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy!

Miss Daisy Is Still Crazy! Ms. Leakey Is Freaky!

Ms. Leakey Is Freaky! The Homework Machine

The Homework Machine Miss Holly Is Too Jolly!

Miss Holly Is Too Jolly! Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire!

Mrs. Meyer Is on Fire! Mrs. Master Is a Disaster!

Mrs. Master Is a Disaster! Ms. Beard Is Weird!

Ms. Beard Is Weird! Shoeless Joe & Me

Shoeless Joe & Me Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda

Funny Boy Meets the Airsick Alien from Andromeda My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green!

My Weird School Special: It’s Halloween, I’m Turning Green! Mrs. Lane Is a Pain!

Mrs. Lane Is a Pain! Miss Klute Is a Hoot!

Miss Klute Is a Hoot! Babe & Me

Babe & Me The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius

The Genius Files 2 Never Say Genius Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic!

Mr. Nick Is a Lunatic! Roberto & Me

Roberto & Me Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy!

Mrs. Lizzy Is Dizzy! Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control!

Mrs. Dole Is Out of Control! Mrs. Patty Is Batty!

Mrs. Patty Is Batty! Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet!

Mr. Granite Is from Another Planet! Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad!

Dr. Brad Has Gone Mad! Mr. Jack Is a Maniac!

Mr. Jack Is a Maniac! Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga

Funny Boy Takes on the Chit-Chatting Cheeses from Chattanooga Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles!

Dr. Carbles Is Losing His Marbles! Abner & Me

Abner & Me Ms. Hannah Is Bananas!

Ms. Hannah Is Bananas! My Weirdest School #2

My Weirdest School #2 The Kid Who Became President

The Kid Who Became President Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal!

Mrs. Kormel Is Not Normal! Getting Air

Getting Air Mission Unstoppable

Mission Unstoppable Nightmare at the Book Fair

Nightmare at the Book Fair License to Thrill

License to Thrill Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy!

Mrs. Jafee Is Daffy! Mr. Sunny Is Funny!

Mr. Sunny Is Funny! Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind!

Mr. Hynde Is Out of His Mind! The Kid Who Ran For President

The Kid Who Ran For President The Genius Files #4

The Genius Files #4 Honus & Me

Honus & Me Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney!

Mr. Tony Is Full of Baloney! Miss Suki Is Kooky!

Miss Suki Is Kooky! Ms. Hall Is a Goofball!

Ms. Hall Is a Goofball! Officer Spence Makes No Sense

Officer Spence Makes No Sense The Pompeii Disaster

The Pompeii Disaster Mr. Will Needs to Chill!

Mr. Will Needs to Chill! Willie & Me

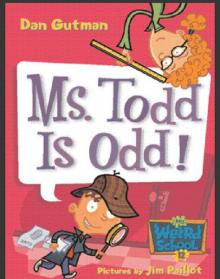

Willie & Me Ms. Todd Is Odd!

Ms. Todd Is Odd!